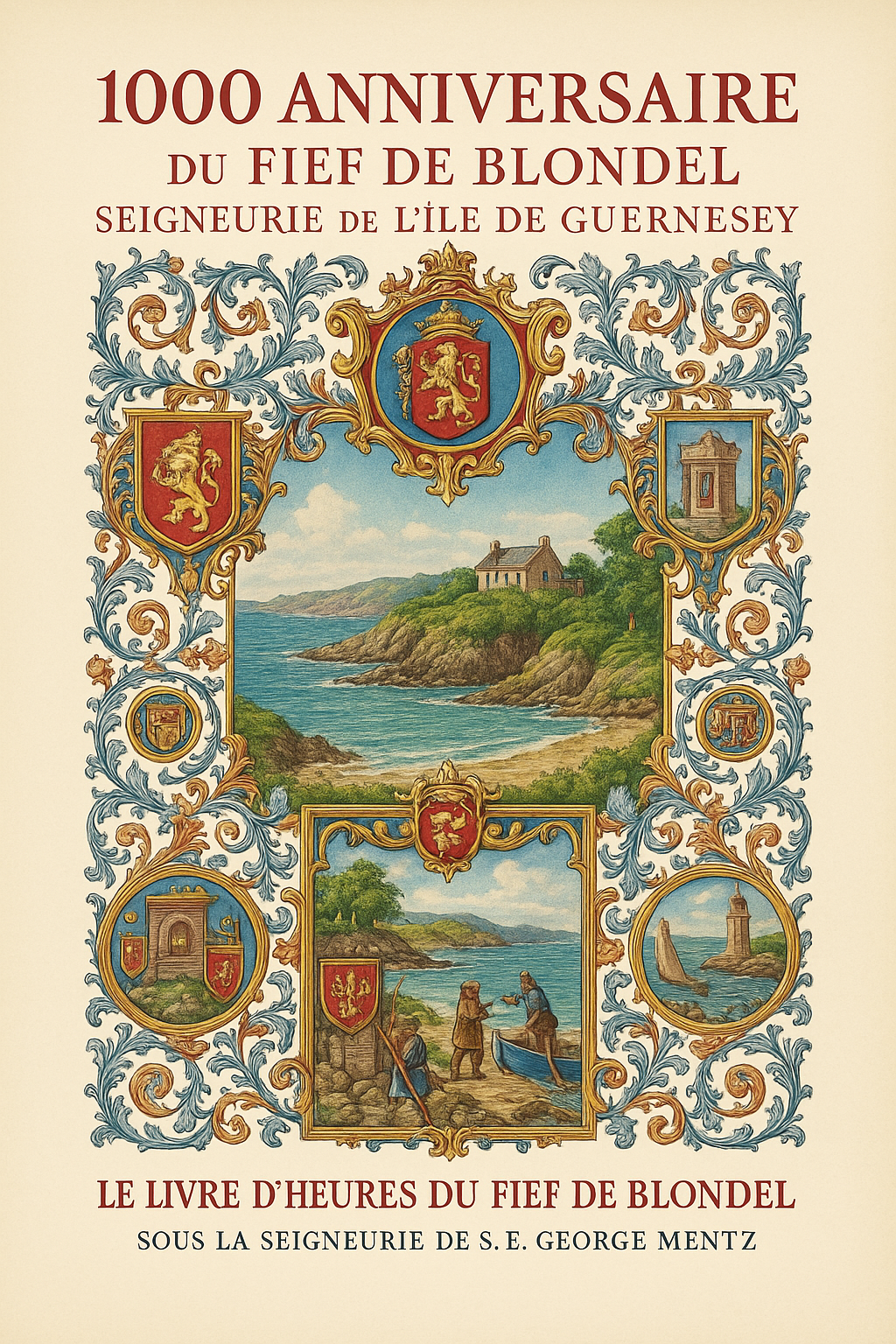

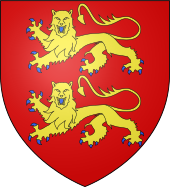

What is a Fief Seigneur in Guernsey and Ancient NormandyI. Origins of the Fief and Seigneurial SystemThe term fief derives from the medieval Latin feudum, meaning a hereditary estate held on condition of allegiance and service. A seigneur—from the Old French seignor, meaning “lord”—was the holder of such an estate. The seigneurial system took root in Normandy after the Viking settlement of 911 AD, when Rollo the Viking, granted lands by Charles the Simple, became Duke of Normandy. Through this grant and subsequent ducal legislation, Rollo and his successors established a hybrid political and legal order combining Norse traditions of land tenure with Frankish and Roman law. In Ancient Normandy, the fief represented both property and jurisdiction. The Seigneur du Fief was not merely a landholder but a minor sovereign within his domain, exercising judicial, economic, and military authority. He could hold a cour du fief (manorial court), collect dues, and owe homage directly to his overlord—whether a count, duke, or the king himself. This created a hierarchical structure of allegiance that formed the backbone of Norman feudal society. II. The Establishment of Fiefs in the Channel IslandsWhen the Duchy of Normandy was formed, the Channel Islands—Guernsey, Jersey, Alderney, and Sark—were gradually integrated into the ducal dominion, particularly after 933 AD, when William Longsword, Rollo’s son, extended Norman control over the Cotentin Peninsula and surrounding islands. From that point forward, the islands were held under Norman law and custom. Each island was divided into a series of fiefs or seigneuries, held either directly from the Duke of Normandy or from a higher-ranking Norman lord. The holders of these lands were known as seigneurs (lords) or dames (ladies). Their estates included both land ownership and legal rights—the ability to hold court, collect rents, and enforce minor justice within their domain. After the loss of continental Normandy in 1204, the Channel Islands remained loyal to the English Crown. The Kings of England continued to style themselves as Dukes of Normandy with respect to these territories, and the feudal system persisted under royal protection. To this day, the monarch is affectionately referred to on the islands as The Duke of Normandy—a title that symbolizes the enduring link between Norman feudal heritage and the British Crown. III. Structure and Rights of a SeigneurA Seigneur of a Fief in Guernsey historically enjoyed a range of seigneurial incidents—rights, dues, and privileges recognized by Norman customary law. These typically included:

The Seigneur’s duties mirrored his privileges. He was bound to maintain loyalty to the Duke (now the British monarch), attend the Court of Chief Pleas, and ensure that justice and order were observed within his seigneury. Unlike English manors, which became absorbed into common law structures, the Guernsey fief

retained its distinct identity as a feudal legal entity. The title “Seigneur” (or “Dame”)

continues to denote ownership of a registered fief recognized by the Royal Court of Guernsey. IV. Legal Recognition and Survival into the Modern EraThe legal existence of fiefs and seigneuries in Guernsey has been continuously recognized from medieval times to the present. Each fief is registered in the Royal Court and subject to feudal dues when transferred. The Feudal Dues (Guernsey) Law of 1980 abolished most feudal payments, such as congé, except when a fief itself is alienated—preserving the ancient practice of paying the Treizième directly to the Crown. Today, there are approximately 75 recognized fiefs in Guernsey, of which around two dozen remain privately held. The rest are vested in the Crown. The holders of these private fiefs still bear the style Seigneur or Dame and, in certain ceremonial contexts, retain a place in the Court of Chief Pleas of the Royal Court. The modern Seigneur du Fief thus embodies both historical continuity and symbolic nobility, linking the present era with Guernsey’s medieval legal traditions. Ownership of a fief remains a matter of real property law rather than peerage, but it carries with it cultural prestige, lineage significance, and an enduring connection to the Norman legal heritage. V. Distinction Between Fief and BordierA related but distinct term often encountered in Norman and Guernsey records is bordier or bordage, meaning a smaller holding or tenement leased from a seigneurial fief. A bordier was a tenant farmer, not a seigneur. The confusion between the two arises because some estates historically described as bordages were later elevated in status to full fiefs, while others remained subordinate holdings. The essential distinction is one of tenure and sovereignty:

In this way, the seigneur stood at the apex of a pyramidal structure of land tenure—an echo of the feudal order that shaped medieval Europe. VI. ConclusionThe Fief Seigneur of Guernsey and Ancient Normandy represents one of the last living embodiments of the feudal order in the Western world. It is both a legal construct and a cultural legacy—a surviving expression of the hierarchical landholding and local sovereignty that defined medieval governance. In Normandy, these institutions gave rise to the great baronies and duchies that shaped European history. In Guernsey, they endured across centuries of political change, protected by law, custom, and the enduring title of The Duke of Normandy. Today, when a modern seigneur pays treizième to the Royal Court, he symbolically renews a tradition that began with Rollo the Viking, the first Norman Duke. The Fiefs of Guernsey stand as living monuments to the continuity of Norman law, local autonomy, and the heritage of European nobility—preserved not in museums, but in the land itself.

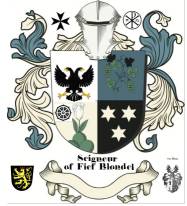

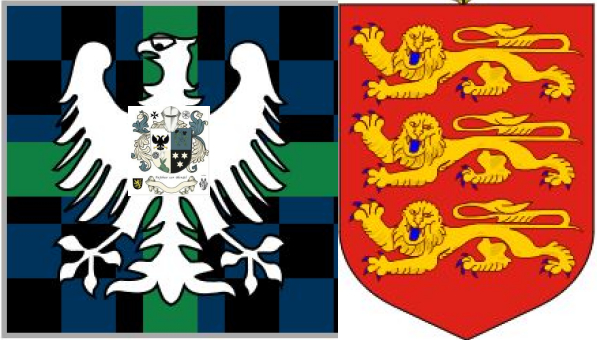

The Fief Seigneur: Royal Tenure, Jurisdiction, and Manorial Incidents in Guernsey and Ancient NormandyI. The Seigneur’s Title and Tenure Direct from the CrownA Fief Seigneur in Guernsey and Ancient Normandy is a Free Lord who holds his title, land, and dignities directly from the Sovereign—originally the Duke of Normandy and later the King or Queen of England, in their capacity as Duke of Normandy. This tenure is the oldest and purest form of freehold ownership known in Western Europe, predating modern common law and parliamentary titles. Under the feudal system established by Rollo the Viking (Duke Rollo, c. 911–930 AD), and codified by his successors, all land flowed from the Duke or King. A fief granted “in fee simple and by right of seignory” created a perpetual hereditary lordship, known as a Free Seigneurie. Such seigneurs—often termed Free Lords, Freiherren in the Germanic tradition, or Friherrer in the Danish-Norse—were tenants-in-chief of the Crown, meaning they owed no intermediate lord. The act of tenure was cemented by the homage and fealty ceremony, during which the Seigneur placed his joined hands between those of the Duke or King, declaring loyalty and receiving symbolic investiture of his lands, often through a staff, stone, or banner. Through this solemn ritual, the Seigneur became a freeholder under the King himself, with perpetual rights and responsibilities that endured through dynasties and conquests. II. Ownership and Territorial SovereigntyThe Fief Seigneur holds true ownership of the land within his domain—not as a tenant at will, but as a hereditary possessor of territory granted “to him and his heirs forever.” The fief included all soil, trees, minerals, meadows, watercourses, and foreshore rights within its boundaries. In Guernsey, this legal status remains recognized. Each fief is registered in the Royal Court of Guernsey, where the Seigneur’s title is confirmed, and dues are paid directly to the Crown Receiver-General when the fief is conveyed. Thus, even in modern law, the Seigneur of a fief stands as a freeholder in chief, deriving title directly from the Crown. Historically, these fiefs were not symbolic honors but real jurisdictions. The Seigneur had administrative, judicial, and economic powers within his lands. The boundaries of each fief defined both ownership and authority—marking the Seigneur’s miniature realm within the greater feudal kingdom. III. Jurisdictional Rights: Courts and JusticeAmong the most important privileges of a Fief Seigneur was the right of court—the power to administer justice and uphold the king’s peace within the fief. The Seigneur could convene various courts, most notably:

These courts often met in a designated “Plaids Room” or open-air bench known as a Court Stone (Banc du Seigneur), still visible in parts of Guernsey and Jersey. The Seigneur’s officers—Seneschal, Provost, Sergeant, and Greffier—served in the administration of these courts. The Seigneur also held police and inspection powers within his fief, ensuring weights and measures were fair, roads and waterways maintained, and public order preserved. In this way, the Seigneur functioned as both magistrate and governor of his small dominion. IV. Economic Rights: Markets, Fairs, and FranchisesBy virtue of royal charter or ancient prescription, a Seigneur could hold markets and fairs within his fief. This franchise of market allowed him to:

These rights, known collectively as royal franchises, were often hereditary and exclusive. In some Norman fiefs, the Seigneur also possessed rights to fishing waters, mills, bakeships, ferries, and toll bridges, as well as rights to wreck of the sea (varech), meaning he could claim shipwrecked goods or timber that washed ashore upon his coast. The Seigneur’s patronage rights (advowson) also extended to local chapels or churches founded on his land, granting him authority to nominate the parish priest or chaplain, subject to episcopal approval. This right of spiritual patronage linked the Seigneur’s domain to the Church, blending sacred and secular governance in the medieval order. V. Manorial Incidents and DuesIn addition to jurisdiction and franchise, a Fief Seigneur enjoyed a range of manorial incidents—customary rights and payments arising from the land and its tenants. The principal incidents included:

Together, these rights formed the economic foundation of seigneurial authority, supporting both the Seigneur’s household and his obligations to the Crown. VI. The Seigneur’s Dual Role: Steward and SovereignThe Seigneur of a fief was both subject and sovereign—bound by homage to his King, yet exercising sovereign powers within his domain. His position represented a delegation of royal authority, allowing the realm to be governed locally through loyal freeholders. In Norman law, the Seigneur’s rights were considered inalienable attributes of his dignity. His authority to hold courts, collect rents, and grant patronage was not mere privilege, but a component of his hereditary sovereignty—imperium in parvo (“sovereignty in small measure”). Even in modern times, Seigneurs are recognized as Free Tenants of the Crown, holding their land in perpetuity, registered by deed in the Royal Court of Guernsey, and owing no superior other than the monarch. VII. The Enduring LegacyThough most feudal incidents have been abolished elsewhere in Europe, the Channel Islands preserve the living legacy of Norman law. The Seigneur’s role—though largely ceremonial today—remains a legal title of dignity, recorded in the Court Rolls and acknowledged by the Crown. A few seigneuries, such as the Fief Blondel, Fief Sausmarez, and Fief Le Comte, continue to maintain their historical estates, court rights, and seigneurial traditions. When homage is rendered or treizième is paid in the Royal Court, the ancient relationship between King and Free Lord is renewed—linking the modern era to the age of Rollo, William the Conqueror, and the great Norman dukes. Thus, the Fief Seigneur stands as both landowner and lord, a living embodiment of medieval continuity—a freeholder direct from the Crown, owning not only the soil beneath his feet but the honor, justice, and heritage that come with it. |

FiefSeigneur de la Fief of Blondel Fief Blondel L'Eperons Lord Baron Mentz of Fief Blondel Geurnsey Crown Dependency > Fief Seigneur Fief Seigneur Seigneurs and Dames Travel Research Lord Paramount Feudal Barons The Seigneur Order Patron George Mentz Charter of Liberties Deed & Title Fief Blondel Islands Viking Kingdom Fief Worship Fiefs of the Islands ECS Extended Continental Shelf Styles and Dignities Territorial Waters Blondel Privy Seal Fief Bouvees of Fief Thomas Blondel Guernsey Court of Chief Pleas Fief Court Arms Motto Flower Fief de l'Eperon La Genouinne Kingdom of West Francia Fief DuQuemin Bouvée Phlipot Pain Bouvée Torquetil Bouvée Bourgeon Bailiwick of Ennerdale Channel Island History Fief Direct from the Crown A Funny Think Happened On the Way to the Fief Guernsey Bailiwick of Guernsey - Crown Dependency Confederation des Iles Anglo-Normandes Sovereignty Papal Bull Research Links Norse Normandy Order of the Genet Order of the Genet Order of the Star Est. 1022 Knights of theThistle of Bourbon Count of Anjou Fief Rights Blondel and King Richard Press Carnival Manorial Incidents Appointments of Seigneurs Store Portelet Beach Roquaine Bay Neustrasia Columbier Dovecote Fief Blondel Merchandise Fief Blondel Beaches Islands Foreshore Events Fiefs For Sale Sold Lords of Normandy Fief Coin Viscounts de Contentin Fief Blondel Map Feudal Guernsey Titles Board of Trustees The Feudal System Hereditaments Chancellor Flag & Arms Fief Videos Guernsey Castle Sark Contact Advowson Site Map Disclaimer Freiherr Livres de perchage Lord Baron Longford Income Tax Guernsey Valliscaulian Order Saint Benedict of the Celestines Society of Divine Compassion Dictionary Count of Mortain Seigneur de Saint-Sauveur Seigneur of Fief Ansquetil Top Success Books Datuk Seri George Mentz Order St. Benedict OSB Celestines Order of the Iron Crown Order of the White Falcon Colonel Mentz Order Red Eagle Order St. Louis Order Holy Ghost Order of Saint Anthony Order of the Black Swan Order of St Columban Order of the Iron Helmet Livonian Brothers of the Sword Fief treizième and Direct from Crown Scotish Barony Info Prince of Annaly Teffia Ireland Valuation

Feudal Lord of the Fief Blondel of the Nordic Channel Islands Guernsey Est.

1179

Feudalherr - Fief Blondel von der Nordischen Insel Guernsey Est. 1179

New York Gazette - Magazine of Wall Street -

George Mentz -

George Mentz - Aspen Commission - Mentz Arms

Counselor George Mentz Esq. - Seigneur Feif BlondelBaron Annaly Baron Moyashel Grants to Delvin About Longford Styles and Dignities The Seigneur Court Barons Fiefs of the Islands Longford Map The Island Lords Market & Fair Fief Worship Channel Island History Fief Blondel Lord Baron Longford Fief Rights Fief Blondel Merchandise Events Blondel and King Richard Fief Coin Feudal Guernsey Titles The Feudal System Flag & Arms Castle Site Map Disclaimer Blondel Myth DictionaryMentz Scholarship Program 101 Million Donation - Order of the Genet Knighthood |

George Mentz Education -

Commissioner George Mentz

-

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/commissioner-george-mentz-clinches-influencer-180000705.html

-

George Mentz News -

George Mentz Net Worth - George Mentz Noble Tilte -

George Mentz -

George Mentz Trump Commissioner -

George Mentz Freiherren Count Baron -

George Mentz Global Economic Forum -

George Mentz Donates Millions